The policy world has a strange way of misallocating attention. Major, systemic problems languish in obscurity for years; relatively minor issues attract armies of experts and millions in funding. As an economist friend once told me, there’s no efficient market for wonkery.

This mismatch creates opportunity. There are whole areas of research out there just waiting for their champion. I’ve encountered a few in my work—and unfortunately, I don’t have the bandwidth to pursue all of them myself. So, in the hope that it spurs someone to take them on, I’m sharing three ideas here.

Idea 1: What Happened to the Davies List?

Back in 2001, Terry Davies and Resources for the Future dropped what is still the best permitting paper ever written. For the uninitiated, Davies is a legend of environmental policy—he wrote the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), more or less co-founded the EPA, and was influential in the design of the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act.

The aptly-named “Reforming Permitting” spans 104 pages and probably has my favorite opening line ever…

But I digress.

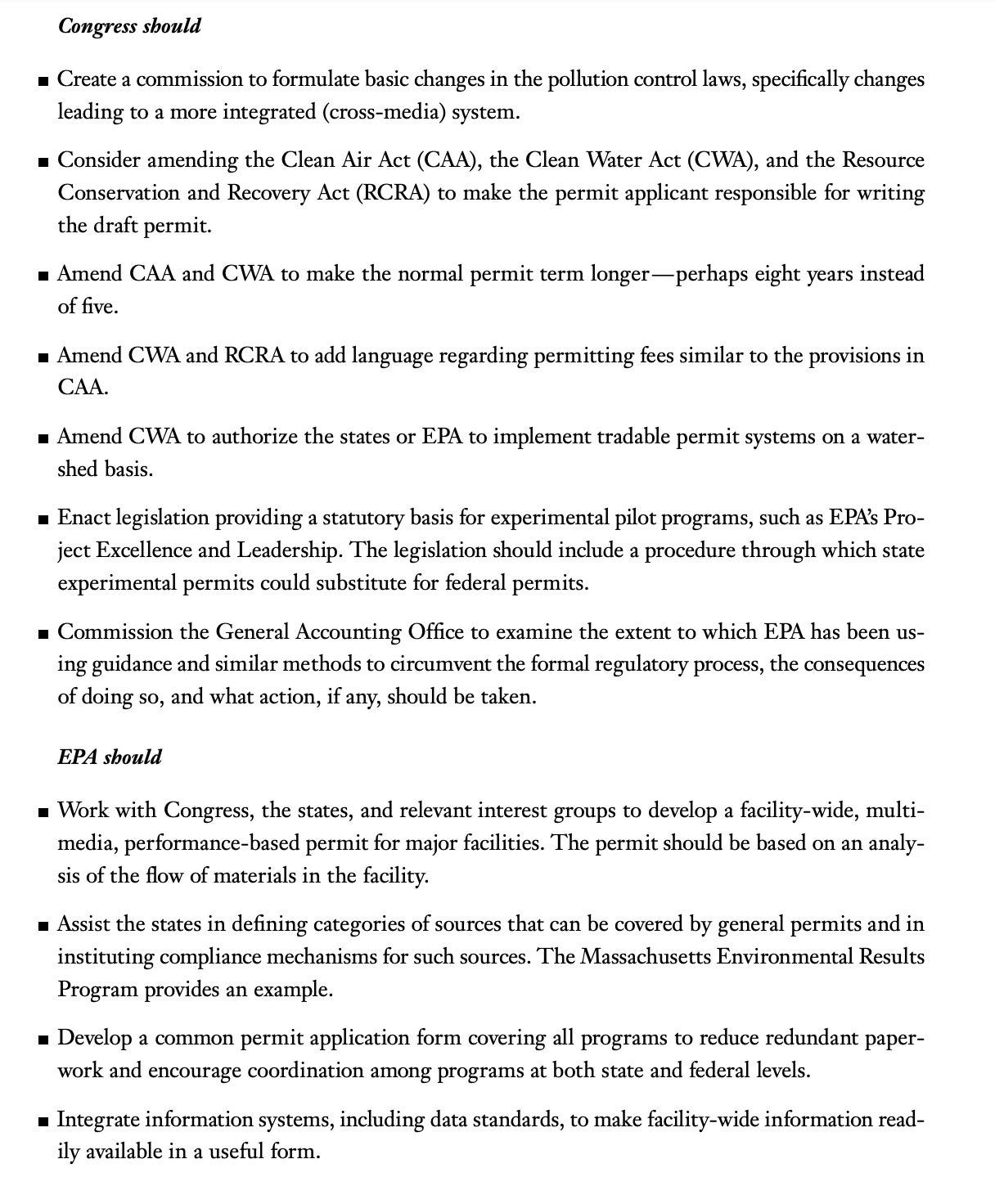

The most relevant part is this: the Executive Summary has two pages of recommendations for Congress, EPA, states, industry, and environmental groups.

A few things here:

First, 24 years later, approximately zero of these recommendations have been adopted. Almost all of these ideas are still relevant, too, from the Clean Air Act’s permit terms to multi-media permitting. So I think it would be fascinating to know where the disconnect was—after all, RFF was quite an influential think tank around the turn of the millennium, and Davies in particular had worked in EPA, CEQ, and “virtually [every] committee or group that has tried to look comprehensively at the base of our environmental law.” Did permitting reform just not feel urgent in Congress in 2001? Did the mess of Project XL and the Common Sense Initiative poison the well? I’d love to know.

Second, we seem to have forgotten about these ideas. Nobody in the current permitting reform discussion seems to be talking about experimental pilot programs or tradable permit systems. Why is that? I have a guess or two—for example, the new generation of permitting reform advocacy has largely emerged out of a desire to fight climate change, which has shifted attention away from pollution control laws and towards procedural laws like NEPA, the Endangered Species Act, and the National Historic Preservation Act. But still, it’s fascinating and befuddling that there seems to be no continuity or development in ideas from the last “golden age” of permitting reform (late 90s-early 2000s) to the current one.

Finally, Davies lays out his ideas in brief in the executive summary—but each one of them could be built out on their own in a research paper. This, in particular, seems ripe for the picking.

Idea 2: What The Hell Happened to Project XL?

Project XL was developed in the Clinton years as part of their "reinventing government" push. EPA career staff quickly developed a motto for the initiative: "If it's not illegal, it's not XL."

In theory, Project XL was simple: EPA would give companies regulatory flexibility if they could demonstrate superior environmental performance. The poster child for this approach was Intel's fab in Aloha, Oregon. Rather than getting a new permit every time they wanted to tweak their manufacturing process, Intel got a flexible permit that set overall emission caps and pre-approved certain production changes. The results were staggering: VOC emissions dropped by 70%, the facility could make 150-200 operational changes annually without permit reviews, and Intel kept investing in Oregon rather than moving operations overseas.

But EPA was flying by the seat of its pants. Environmental statutes like the Clean Air Act don't actually give EPA authority to waive regulations just because a company promises to do better. Instead, the agency was relying on “enforcement discretion”—basically a gentleman’s agreement with facilities to not enforce regulations so long as the facility complied with the terms of the XL agreement. This assurance only went so far, however, as there was nothing stopping citizens from suing the facility for the very violation that the EPA was agreeing to ignore.

EPA’s other idea was “site-specific rulemaking,” in which EPA could promulgate a new regulation specifically for an individual XL project. This offered more legal protection than the enforcement discretion approach, but it was also incredibly expensive. The Administrative Procedure Act requires agencies to go through several steps to promulgate a new rule, including the whole notice-and-comment process.

As a result, companies looking at Intel's success had to weigh it against months or years of regulatory uncertainty. Then, in 2000, Republicans took control of Congress. Project XL was tied to the Clinton presidency, and Republicans had no plans to help the Clinton EPA by providing clear statutory authority for the program. And that was the end of that.

The Intel case proved that flexible permitting could deliver everything it promised: better environmental outcomes, operational flexibility, and continued U.S. investment. But it also showed that you can't build a durable regulatory program on shaky legal ground, no matter how good the results are.

So, twenty-five years later, I’d love to see someone ask: What would a Project XL look like today? How would we provide that statutory basis? And which of the factors behind Intel’s success would we want to replicate?

Idea 3: Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) Reform

The United States has three major pollution-control laws: the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. There is also the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), which regulates underground injection and is therefore very relevant to carbon storage and enhanced oil recovery, but it has a much narrower scope.

The Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act are well known, regulating air and water pollution, respectively. The RCRA, meanwhile, regulates waste.

The RCRA requires permits for facilities that treat, store, or dispose of hazardous waste, sets standards for how waste must be handled at each stage, and establishes reporting requirements to ensure waste can be tracked throughout its lifecycle. As a result, the RCRA touches every corner of American industry: manufacturing and chemical production, healthcare (think biomedical waste), mining, and the automotive industry.

And, much like the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, the RCRA is mostly delegated to the states, meaning that states have quite a bit of latitude in defining what the RCRA permitting process looks like.

Two things I’ve come across:

RCRA seems to have flexible permits (specifically, permits-by-rule). Are these only federally-issued? Do states create their own? You tell me!

Industry seems to be very upset about the RCRA’s Hazardous Waste Identification Rule (HWIR).

And that’s… all I know! Have at it, people.

I hope one of these gets somebody started. If this goes well, I have more in the hopper that I’ll share down the line.

I’m going to make a WILD guess that the Davies List has stuff relevant to electric utilities.

Time to start digging :)